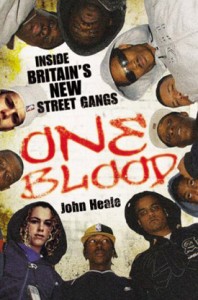

Book – One Blood – Inside Britain’s New Street Gangs – John Heale, 2008.

Book – One Blood – Inside Britain’s New Street Gangs – John Heale, 2008.

This focuses on just some of the themes in this book –

This book is based mainly on interviews with gang members based in London, Manchester, Liverpool and elsewhere in Britain, and provides an empathetic and some may say sympathetic insight into gang life in modern Britain.

Heale focuses mainly on the wider social and economic background in which most of the gang members he interviews have grown up and argues that there is a link between living in a deprived, high crime area with limited opportunities and the emergence of gang culture. One can discern four major reasons why individuals join gangs –

Firstly, Heale reminds us many current gang members, would have been victims of crime numerous times before they joined a gang, and this experience of being a victim of crime, is often what leads people to joining a gang.

Heale uses data from the British Crime Survey to demonstrate how crime is highly concentrated in poorer areas. He points out that if you are a teenage boy living in a gang area, it is a near certainty that you will have been a victim of crime at some point, and probably a repeat victim, In this context, joining a gang makes sense as it is a way of protecting yourself from being a victim of crime – it is a rational response to living in a high crime area.

This is illustrated this by the case of how one 13 year old, Daniel, came to join a gang – It started with him being punched in the face by a member of a gang in a local park. His brother, already a member of another gang, took vengeance on his behalf – in school – which lead to Daniel spending more time with his elder brother – which eventually lead to him getting introduced to his brother’s gang.

Secondly, many of Heal’s interviewees have come from broken families, having parents with drug problems who are disinterested in their children and many youths would have witnessed domestic violence from a young age – and would have grown up with the feeling that nobody really cares about them.

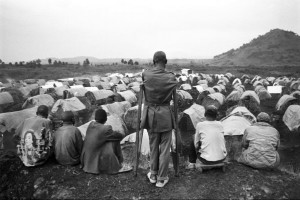

Thirdly, Heale reminds us that living in poverty and being marginalized from the rest of society is normal in gang areas . Following. Gangs typically emerge on sink housing estates – with poor, marginalized people being crammed together in one area. In these areas we have high levels of debt and stress. Today, we have a new generation of kids that have known nothing other than these estates – and it is this generation that are joining gangs.

To illustrate how geographically isolated people on these estates are – Heale points out that the typical gang member has a very local world view – they spend most of their time in their local area and tend to associate their particular territory with their peers and thus with protection and safety – when interviewed, many gang members perceive going to the London Eye as a trip abroad. Gang members don’t generally think outside their local boundaries – and Heale argues that the rest of the country may as well be a different nation as far as he is concerned. He in fact argues that the experience of life in an area dominated by gangs is very different from life in most other parts of Britain.

Finally, there is a lack of legitimate opportunities in the kinds of areas where gangs emerge. Gang members do not see any legitimate opportunities in training or working their way out, and they can earn a lot more money getting involved with selling drugs within the context of a gang. Most gang members see their part of being a gang as a way of ‘getting out’ of the ghetto – as evidence he cites Professor John Pitts who speculates that those at the top of a drugs chain in the Walthom Forest area of London, one could earn as much as £130 000 a year from drug dealing.

Thus the experience of life for a typical person living in gangland today, and for your typical gang member, would have involved being brought up in a broken home, poverty and relative deprivation, being a multiple victim of crime, and one of frustrated opportunities. Heale’s analogy for Gangland is that it is like a ‘boot perpetually stamping on a human face’ – This experience of early socialization encourages individuals to think of the short term – rather than planning for the long term, because for them, there is no long term future, other than prison or death, and this is enough for many people in these gang areas to become emotionally detached from the consequences of their actions.

So according to Heale it is this context of economic and social deprivation that explains why people join gangs and also helps to explain some of the extremely violent crimes that some gang members engage in.