In this latest Thinking Allowed podcast on ‘Low pay, no pay’ Britain Laurie Taylor talks to the sociologist, Tracy Shildrick, about her prize winning study of individuals and families who are living in or near poverty. The research was conducted in Teesside, North East England, and focuses on the men and women who’ve fallen out of old working class communities and must now cope with drastically reduced opportunities for standard employment. To my mind, this is a good in-dept illustration of what life is really like for a section of the Precariat (although Shildrick would be more cautious).

The research is based on the book (published in 2012) – Poverty and insecurity Life in low-pay, no-pay Britain by Tracy Shildrick

This book explores how men and women get by in times and places where opportunities for standard employment have drastically reduced and where people exist without predictability or security in their lives, the book shows how poverty and insecurity have now become the defining features of working life for many.

Work may be ‘the best route out of poverty’ sometimes but for many people getting a job can be just a turn in the cycle of recurrent poverty – and of long-term churning between low-skilled ‘poor work’ and unemployment.

Based on unique qualitative, life-history research with a ‘hard-to-reach group’ of younger and older people, men and women this research challenges long-standing and dominant myths about ‘the workless’ and ‘the poor’, by exploring close-up the lived realities of life in low-pay, no-pay Britain.

Below is a summary of the main points of the podcast

- The low-pay no-pay cycle is much more common than long-term unemployment. Most people intreviewed were committed to work, even though the jobs they did were not ‘comfortable’ jobs. This was one of their most consistent findings…. which in part explains why these people go back time and time again. This of course is the opposite to what we here in the media about people ‘languishing on benefits’.

- It is not a guarantee that taking up employment will mean an individual is going to better off than on benefits. Most people were ashamed at having to claim benefits.

- Jobs typically did not last long enough to take workers away from poverty.

- In work-poverty is – 66% of poverty live in households were at least one person is in-work.

- The types of work include factory jobs, bars, customer service, often run through agencies.

- For the people interviewed these type of jobs are not stepping stones to something better – they get one foot on the rung of the ladder, get knocked off, and have to climb back on again.

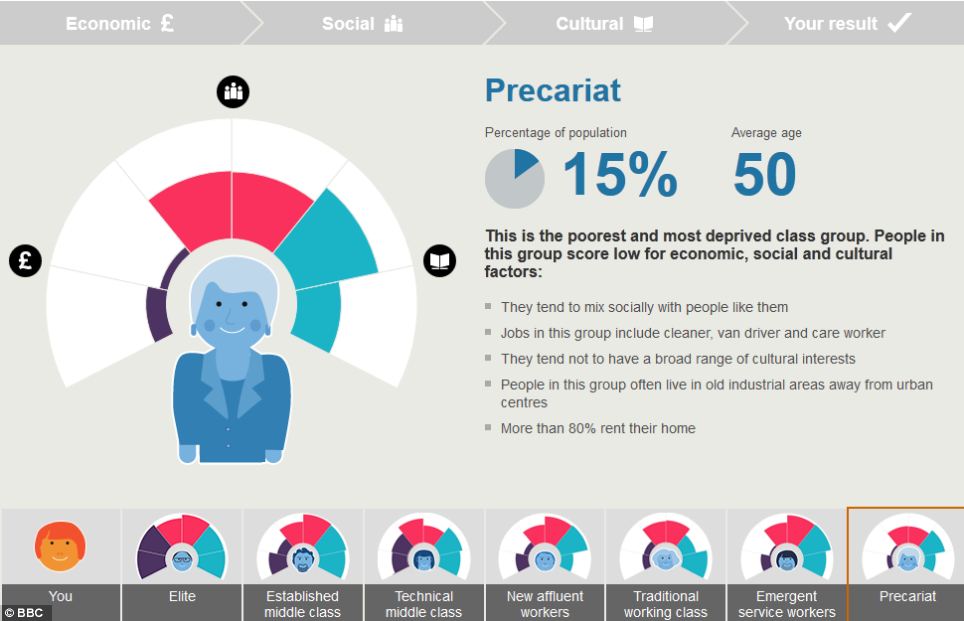

- Shildrick is not convinced that the term ‘Precariat’ is accurate enough to describe adequately the experience of all people who are sometimes put into this category. She argues that the experiences of the people she interviewed are different to those of a graduate working for a few years in similar jobs (although the people she interviewed do seem to fit into the definition of the Precariat used by the GBCS below)

- In response to the idea that better training is the solution to helping people in these jobs, Shildrick suggests we need to look at the bigger picture – society needs these jobs – we need to think ahout how to reward them more appropriately.

Shildrick suggests that it is ultimately employers who have the power to help people out of this cycle. Unfortunately, the trend seems to be of employers being increasingly inflexible while demanding that employees be more flexible.

Links –

1. This seems to be a good in-dept illustration of what life is really like for a section of the Precariat

2. Also a nice illustration of the effects of living in liquid-modernity – The reality is actually bleaker for them than the above research might suggest – As Zygmunt Bauman reminds us (in Liquid Modernity)- ‘The bottom category are the easeist to replace, and now they are disposabe and so that there is no point in entering into long term commitments with their work colleagues….. this is a natural response to a flexibilised labour market. This leads to a decline in moral, as those who are left after one round of downsizing wait for the next blow of the axe.